by Hammed Sonny | Jun 24, 2024 | Africa, Anglophone World

West African Pidgin English (WAPE) is a term for a diverse number of English-based pidgin and creole languages spoken throughout West Africa, of which Krio (spoken in Sierra Leone) is one of those languages. Other types of WAPE languages are Liberian Pidgin English, Nigerian Pidgin English and Cameroon Pidgin English. Pidgin languages in West Africa act as a lingua franca between speakers of different languages, who speak the WAPE languages in addition to other vernacular. In Nigeria alone, there are between three and five million people whose primary language and form of communication is Pidgin, and is estimated to be used as a second language by up to 75 million people in the country (around half of the population). Whilst Sierra Leone Krio is not spoken to the same degree as Nigerian Pidgin English, it is spoken as a second language in Gambia, Guinea and Senegal by an estimated 4 million people.

Are Krio and West African Pidgin mutually intelligible?

Both Krio and West African Pidgin derive from the same language family, English Creole (also known as English-based creole languages). As a result, the majority of the pidgin and creole languages that constitute West African pidgin share the same basic linguistic and phonological characteristics. For instance, many of the WAPE languages share the same vowel inventory, made up of seven vowels: i, ey, e, a, o, ow, u. In addition to this, word formation in the WAPE languages is very similar. The phrase “sit down” in Pidgin English is constructed through complex forms, combining the bound prefix “si-“, meaning “sit”, with the free form “dong”, or “don”. Both Nigerian Pidgin English and Krio translate the phrase “sit down” as “Sidon”. In most of the pidgin languages, there are words, like the word “si”, which are only found in a bound form, meaning that they only occur as part of another word and never on their own.

Another example of the possible mutual intelligibility between Sierra Leone Krio and West African Pidgin is the prominence of the grammatical feature of verb serialization, or serial verb construction. This type of grammar can also be found in many different African languages, namely Yoruba, and is not common in the English language. Serial verb construction refers to a type of grammatical construction in which a sentence contains a subject and different verbs, but these words are not linked by a conjunction (e.g. and, but, if). Therefore, in Yoruba, one would translate the sentence “He brought the book” as “O mu iwe wa” (“He took book come”). In the Krio language, the sentence “I cut the bread with the knife” would be translated as “A tek nef kot di bred” (literally translated “I take knife cut the bread”). Moreover, Krio and the other West African Pidgin English languages share similar pronouns. Some of the Krio pronouns, for instance, are mi (“me, my”), yu (“you, your”), “am” (he/she/it), “dem” (they, them, theirs), “im” (his, hers, its”), “una” (feminine pronoun “you”). These pronouns are all also used in Nigerian Pidgin English as well as Ghanian Pidgin English.

To what extent are these languages not mutually intelligible?

While there are some similarities between Krio and the other West African Pidgin languages, they are not entirely mutually intelligible. To give an example, the most common phrase across the different pidgin languages in West Africa is the greeting. In Cameroonian Pidgin, the phrase “how na” (“how are you”) is used, similar to the Nigerian Pidgin greeting phrase “har fa”, meaning “how far”. However, in Krio, the word “kushe” (pronounced cushah), meaning “hello”, is used as a form of greeting. Ghanian pidgin English also diverts from the rest of the West African Pidgin English languages, especially in the context of greetings, as it utilises loanwords from the Akan languages (most widely spoken languages in Ghana), namely “eti sen” (“how are you”).

The primary pidgin languages in West Africa, like Nigeria Pidgin English, tend to borrow words entirely from the English language and do not utilise many loanwords, inhibiting the extent of intelligibility between the different pidgin languages. Like Ghanian Pidgin English, Krio also borrows loanwords from other languages. One such example of the use of loanwords in Krio is the word “bòku”, meaning “many”. This word derives from the French adjective “beaucoup”, meaning “many” or “lots”. Moreover, Krio has borrowed different idiomatic expressions from other African languages such as Yoruba, Kikongo and Igbo. In Krio, the phrase “big yay” (literally translates as “big eye”) is used to convey greed and selfishness. This idiom is borrowed from the Igbo expression “anya uku” (which literally translates as “eye big”). Similarly, another idiom that can be found in the Krio language is “swit mot” (meaning “sweet mouth”), which is used to convey persuasiveness. This same idiom can be found in Yoruba and the Akan language, as “enu didu” (Yoruba) and “ano yede” (Akan, or Twi).

In Conclusion

The plethora of pidgin languages that constitute the West African Pidgin English languages, such as Nigerian Pidgin English and Krio, derive from the same language family of English Creole and are spoken by millions across West African countries as a lingua franca and second language. They share some vocabulary and phonological similarities, and could be argued to be mutually intelligible to some degree. However, there are definite varieties and divergences between the languages, like Krio’s use of loanwords from other languages as well as its differences in phrases. Therefore, one cannot treat Sierra Leone Krio and Nigerian or Ghanian Pidgin English as the same language, especially in the context of translation or interpretation.

If you should require translation of any of the pidgin languages spoken in the many different countries of the West African region, such as Nigeria, Sierra Leone or Ghana, you may be interested in the excellent services provided by Crystal Clear Translation. At CCT, we employ many efficient and reliable translators able to navigate the intricacies of many different languages and cultures. Click here for a quote if you should need interpretation or translation services in a multitude of different languages.

by Hammed Sonny | Jun 17, 2024 | Africa

The Tuareg people are a Berber ethnic group, who live primarily in Sub-Saharan and Northern Africa (such as Niger, Mali, Burkina Faso, Algeria, Nigeria), whereas the Fulani people live in West Africa and Central Africa (such as Guinea, Senegal, Mali, Mauritania, Gambia). Regarding population size, there an estimated 2 million Tuareg people, and, by contrast, at least 25 million people within the Fulani ethnicity. Both groups are traditionally pastoralists and nomadic people, and have historically, both peoples have previously utilised a hierarchical caste system, with divisions between those viewed as the nobles, the artisan caste (blacksmiths, jewellers) and those who were enslaved (the Maccudo in Fulani, and the Ikelan in Tuareg). Whilst most Fulani and Tuareg people now live within urban populations in various African countries, there are still some who live as herdsmen and agriculturalists.

What are some of the similarities and differences between the Tuareg and Fulani people?

Both the Tuareg and Fulani are followers of Sunni Islam. In fact, around 99% of Fulani people are estimated to be practising Muslims. Originally the Tuareg people followed the traditional Berber religion, but adopted Islam in the 7th century, followed by Sunni Islam in the 16th century. Despite the predominance of Islam within the Tuareg, they have also preserved pre-Islamic beliefs in spirits and exorcism. In addition to this, they differ to traditional Islam in some of their practices. For instance, as part of their ancient traditions, Tuareg men wear a veil. Tuareg men must wear the veil for the duration of their lives from the age of 25 onwards and cannot remove the veil. The wearing of the veil is supposed to symbolise the passage from childhood to adulthood. However, as the number of Tuareg living a nomadic lifestyle declined, fewer Tuareg men wear the veil, although it is still worn for festive and ceremonial events within the Tuareg community. The Tuareg belong to the Maliki school of Islam and are not as orthodox in their practise of Islam. They have daily prayers for instance, but are not required to fast during Ramadan, mainly due to the traditionally nomadic nature of their lifestyle which meant they had to travel often.

In contrast to the Tuareg, the Fulani practise a more traditional form of Sunni Islam, and have incorporated more characteristics of traditional Islam, such as the practise of women wearing the hijab and burqa. In a historical context, the Fulani people are believed to be part of the first Africans to convert to Islam. During the eighth and fourteenth centuries, there were a group of Fulani Islamic clerics known as the Torodbe, who acted as missionaries of the Islamic religion. The Fulani empire (also known as the Sokoto Caliphate) played an important role in the spread of Islam throughout Western Africa during the early nineteenth and twentieth centuries.

One other major difference between the Tuareg and Fulani people is the languages spoken by the two groups. The Tuareg speak the Tuareg language, which consists of different dialects known as Tamasheq, Tamahaq, Air Tamajeq and Tawellemet. These different dialects derive from the Berber language family, itself part of the Afro-Asiatic language family. The Berber languages also include Tarifit and Kablye. which are spoken mainly in Morocco and Algeria. The Tuareg language is written in three different scripts, Tifinagh, Latin and Arabic. The Tifinagh script, which is written from left to right, is the original alphabet of the Tuareg people, and derived from the ancient Libyan alphabet. Unlike Latin, the written Tifinagh alphabet only includes consonants. This kind of writing system is known as an abjad, which is also used in the Hebrew and Arabic languages.

On the other hand, the Fulani people speak the Fula language, part of the Senegambian branch of Niger-Congo language family. The Fula language is written mainly in the Latin script but is also written in Arabic and the Adlam script. Whilst the Fulani people predominantly use the Latin and Arabic scripts for written communication, the Adlam script was created in 1989 by Ibrahima and Abdoulaye Barry, specially for the Fulani language. This alphabet is written from left to right and is composed of 28 glyphs (5 vowels and 23 consonants). Adlam is taught in schools in Guinea, Nigeria, and Liberia, and has also been used in the publication of newspapers and books. In addition to the Fula language, the Western Fulani people (in Senegal, Mauritinia, Gambia and Western Mali) speak a language known as Pulaar. This dialect is the second most spoken language in Senegal, being spoken by around 22% of the population. Like Fula it is written in the Latin and Adlam scripts but is also written in an Arabic script known as Ajami (this script is also used in Swahili and the Hausa language).

In Conclusion

There are numerous differences between the Fulani and Tuareg tribes, in their different languages and within the practice of their Sunni Islam religion. Whilst both groups share historical similarities in the structure of their societies as well as their traditional livelihoods as nomads and farmers, the modern Tuareg and Fulani people are distinct groups pf people with a rich and varied culture and history. If you require translation or interpreting services for someone of the Tuareg or Fulani groups in their respective languages, or any other language, you can get a quote here from Crystal Clear Translation.

by Hammed Sonny | Jun 3, 2024 | Africa, Arab

The North African country of Algeria and its rich tapestry of dialect is a fascinating point of interest. With an extensive history and a multitude of culture and communities, we are going to strip it back and take an insightful look into the languages of Algeria.

The official languages of Algeria are Arabic and Berber (Tamazight). A staggering 99% of Algerians speak Arabic or Berber as their native tongue.

Arabic in Algeria

Since 1963, Arabic has had official language status in Algeria. It is estimated that 81% of the Algerian population speak this form of Arabic as their native dialect. Non-native speakers will typically learn literary Arabic in school.

Within the country, Arabic is widely used within many official settings including the media and government; with formal documents being printed in the language.

The Algerian variation of Arabic differs from standard Arabic in the sense that the standard version is typically reserved for official purposes, whereas Algerian Arabic is utilised more commonly in day-to-day settings- making it slightly more informal.

Berber in Algeria

In more recent, times Berber has taken its stance as Algeria’s second official language. Based on location, there are 5 different strands or dialects of the Berber language family. Berber speakers are most prevalent within areas such as Kabylia, the Algerian Saharah desert and Awras.

It was only in 2016 that Berber became recognised and was given official status. However, it has been spoken since the medieval times in Algeria. It is interesting to note that despite its extensive background in getting official recognition, Berber has in fact greatly influenced the vocabulary and grammar of Algerian Arabic- this means that to an extent, the two languages are mutually intelligible.

The Status of French in Algeria

Although French has no official status throughout Algeria, it is still widely used to this day. French is part of a typical school curriculum in Algeria, with around 18 million Algerian citizens able to read and write in French- this accounts for about half of the country’s entire population. This shouldn’t come as too much of a surprise, as French is one of the most richly spoken languages in the world.

Smaller regional languages

Alongside the larger, more greatly spoken dialects, many smaller regions are rife with their own languages. Some of which include: Hassaniya and Korandje- both of which are heavily influenced by Arabic and Berber.

Final thoughts

With both Arabic and Berber accounting for the majority of native tongue in Algeria, Algerian Arabic is the dominant language in both community and work settings. Even native Berber speakers are able decipher the language- meaning the high degree of mutual intelligibility allows for ease of communication amongst all Algerian people.

Do you require our services?

If you require an Arabic interpreter or translator, visit Crystal Clear Translation for a quote.

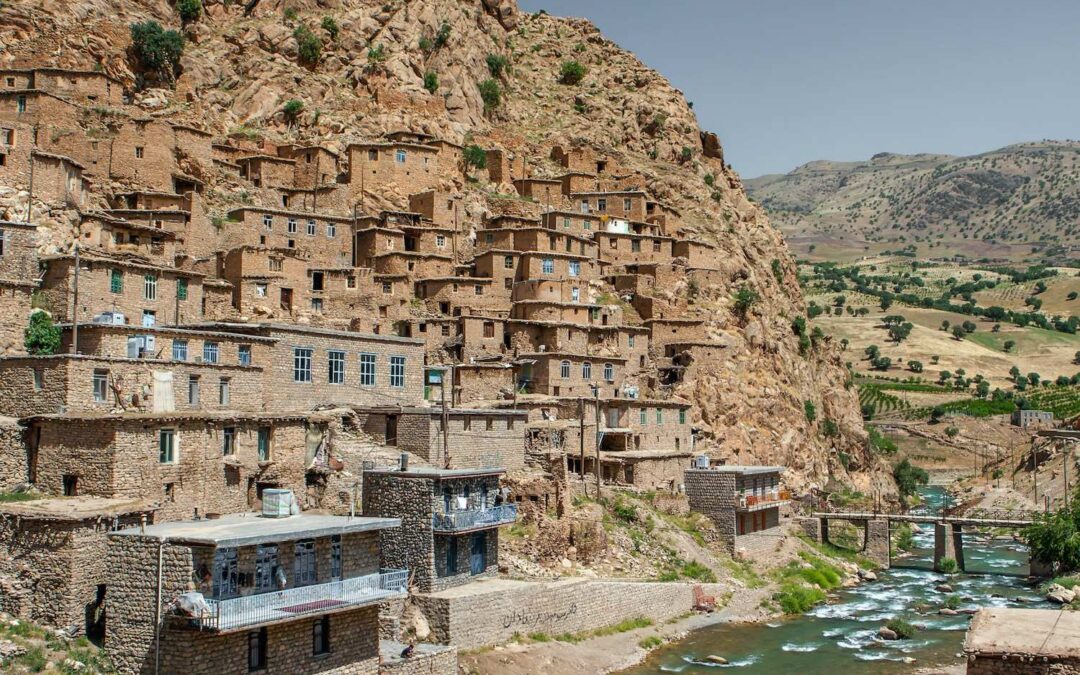

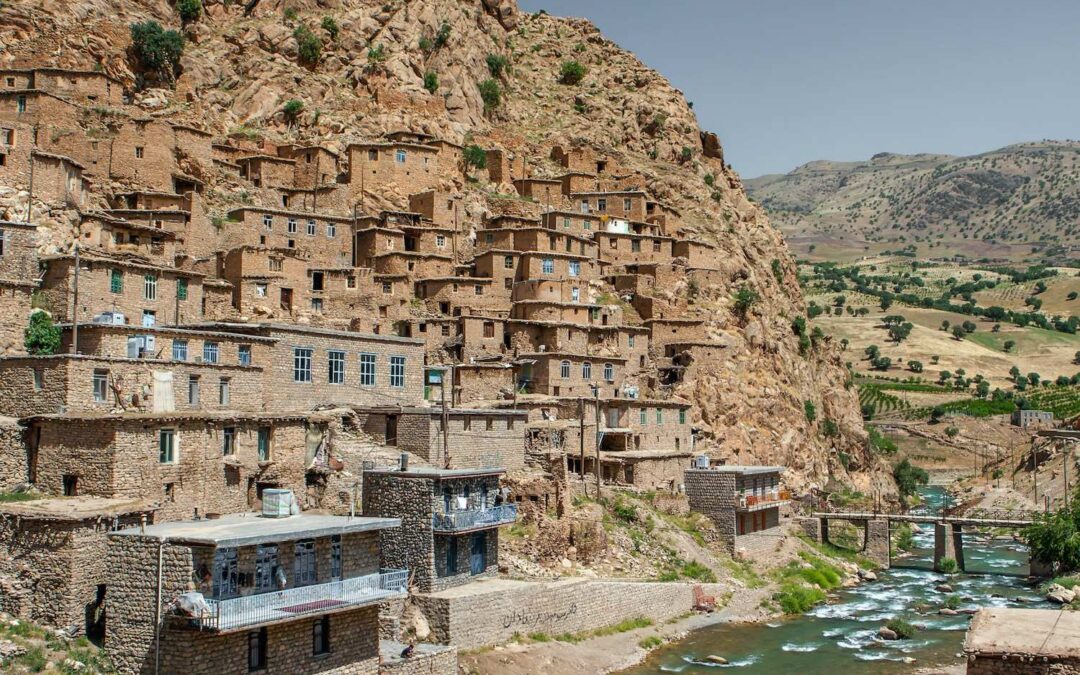

by Hammed Sonny | May 27, 2024 | Asia

Kurmanji derives from the Kurdish language family. Sometimes known as northern Kurdish, Kurmanji is a language commonly spoken in southeast Turkey and Northern Syria. Out of all the Kurdish dialects, Kurmanji is the most widely spoken, with approximately 15 to 20 million native speakers combined.

History of Kurdish people (The Kurds)

There is not a great deal of information readily available about the background of the Kurds, however there are a few important points that we can note.

Kurdish people were found to be living within the mountains of Anatolia. It was here that dialects like Kurmanji were first heard of and have since evolved into modern tongues over the years.

Kurmanji in Syria

Kurds within Syria reside mostly in three regions of northern Syria close to the Turkish border. They make up the largest ethic minority, however the population is considerably less than that of Turkish Kurds. Out of the Syrian Kurd population, the most part will speak Kurmanji.

Kurmanji in Turkey

The majority of Kurmanji speakers live within the south-eastern area of Turkey and is the largest minority language within the country. Around 8 to 10 million Kurds in Turkey speak Kurmanji as their native tongue.

How is Kurmanji written?

The Kurdish dialect mainly written following the Latin alphabet in both the Turkish and Syrian variations. Although this is utilised widely, it is not classified as the standardised alphabet of the language. It is also not unheard of for Kurdish people to use the Cyrillic and Arabic scripts. Kurmanji differs completely to other Kurdish dialects that commonly use old Yazidi script.

Although the Latin alphabet is heavily used, English speakers would find it challenging to decipher the language due to meanings and pronunciations of words.

Below is an example of the Kurdish alphabet (deriving from Latin):

Examples of Kurmanji phrases:

Rojbash- Hello (formal greeting)

Shevabash- Goodnight

Saet çend e? – What time is it?

Grammar

The structure of grammar is quite complex, which also makes it less intelligible to the English. The grammatical aspects of Kurmanji are unique. In terms of difficulty, it is thought to be a hard language to learn.

Intelligible or Unintelligible?

Kurmanji dialects like that of Turkish and Syrian are considered to be mutually intelligible, as there is very little differences between them. Although there may be an occasional unique word or pronunciation, each dialect is almost identical. Kurmanji is in fact a group of dialects, but due to their striking similarities, most Kurds will state that they simply speak Kurmanji.

Concluding thoughts

It is apparent that the Kurmanji language is very intricate and unique, and although there is not a great deal of research readily available to us, we can still conclude that both Turkish and Syrian Kurmanji are extremely intelligible between regions. However, the language is not as intelligible to those who speak a different native tongue.

Do you require our services?

Should you require assistance with a translator or interpreter, visit Crystal Clear Translation for a quote.

by Hammed Sonny | May 20, 2024 | Europe

The Albanian language has over 7.5 million native speakers across a multitude of regions. It is of course the official language of Albania but is also considered the official tongue in the state of Kosovo.

Kosovo Albanians

Kosovo lies in the southeast of Europe, in the centre of the Balkans. With a population of approximately 1.6 million throughout the region, the richly populated state is home to the Kosovo Albanians- the largest ethnic group in Kosovo. According to the most recent census carried out, native Albanian speakers accounted for around 82% of the population.

Albanian spoken in Kosovo vs in Albania

In terms of culture, Albanians in Albania and Kosovo are considered closely related. However, in terms of dialect they do differ.

Tosk

Tosk Albanian belongs to the southern group of dialects from the Albanian language family. Tosk is spoken richly throughout Albania, and it forms the foundation of the standard form of the language. 1.8 million people speak Tosk as their native language; mostly within Albania although it is spoken in small clusters throughout Italy, Turkey and North Macedonia.

Gheg

Gheg Albanian is the second major Albanian dialect; typically spoken by Kosovo Albanians through the state of Kosovo. It is a northern dialect, and has official status throughout Kosovo- however, this only accounts for the spoken form, written Gheg does not have the same status but is still used within written media.

Differences and Similarities between Tosk and Gheg

With the main difference between the two Albanian dialects being their regional status, there are a few other differing factors. Dependent on the specific region you are in, the Albanian grammar may stay the same, but the accent and pronunciation may change. This can mean that a Kosovar Albanian may not be able to decipher that a Tosk Algerian is saying in a sentence. However, in written form there is still a high degree of mutual intelligibility.

In terms of vocabulary, the two are incredibly similar with only very minor differences.

Final thoughts

Albanian and Kosovan Albanian are incredibly similar in written form. When being spoken, there may be some degree of understanding, but small difficulties may occur based upon region. Tosk and Gheg remain as their own languages within the Albanian family of dialects.

Do you require our services?

Should you need an Albanian interpreter or translator, visit Crystal Clear Translation for a quote.